taniwha (water monster), TarraWarra Biennial 2023: ua usiusi faʻavaʻasavili, curated by Dr Léuli Eshrāghi.

Dr Kirsten Garner Lyttle

Artist Statement for TarraWarra Biennial 2023: ua usiusi faʻavaʻasavili, curated by Dr Léuli Eshrāghi.

Title: taniwha (water monster)

A quick google image search of “taniwha” will show illustrations of dragon-like creatures, often depicted in bodies of water (oceans, lakes, rivers etc.) According to the Te Aka Māori Dictionary “taniwha” means;

(noun) water spirit, monster, dangerous water creature, powerful creature, chief, powerful leader, something or someone awesome - taniwha take many forms from logs to reptiles and whales and often live in lakes, rivers or the sea. They are often regarded as guardians by the people who live in their territory, but may also have a malign influence on human beings.

Some taniwha are kaitiaki (guardians), others man-eaters. Taniwha can be reptile-like, have wings, or take the form of dolphins, whales, sharks, octopuses and eels. Some consider viruses such as 1918 influenza or more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic to be taniwha. Taniwha are also known to shapeshift between forms. For example, an upright log travelling against the current in a river is a sign of taniwha. Oral histories tell of the movements of taniwha carving waterways and mountains throughout Aotearoa and Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa (The Pacific Ocean). Some argue that taniwha have caused earthquakes, aftershocks, eruptions and tsunamis’. Taniwha are an elemental danger; an ominous malevolence attached to a place. Tohunga (healers/priests) used offerings to placate taniwha, or recited spells, prayers and incantations to put a taniwha to sleep or even to death.

A proverb from my iwi (tribe) and awa (river), Waikato states;

“Waikato taniwha rau, he piko he taniwha.”

Waikato of a hundred taniwha, every bend a taniwha.

Does this refer to the twisting dangerous path of the Waikato River, filled with unknown monsters? Or is this instead a comment on the powerful chiefs in this area? Can both interpretations be true?

Using found news articles of actual reported taniwha sightings dating from 1886 through to 2019 in combination with photographs of potential taniwha, this series of photographic prints attempts to show that although taniwha may be murky and opaque in nature, it is naive to dismiss them as fictious, exaggerated or mythological. Although difficult to see, or read, taniwha continue to play an important role in cultural identity for many Māori iwi.

Install Image by Andrew Curtis

Native Braves Taniwha

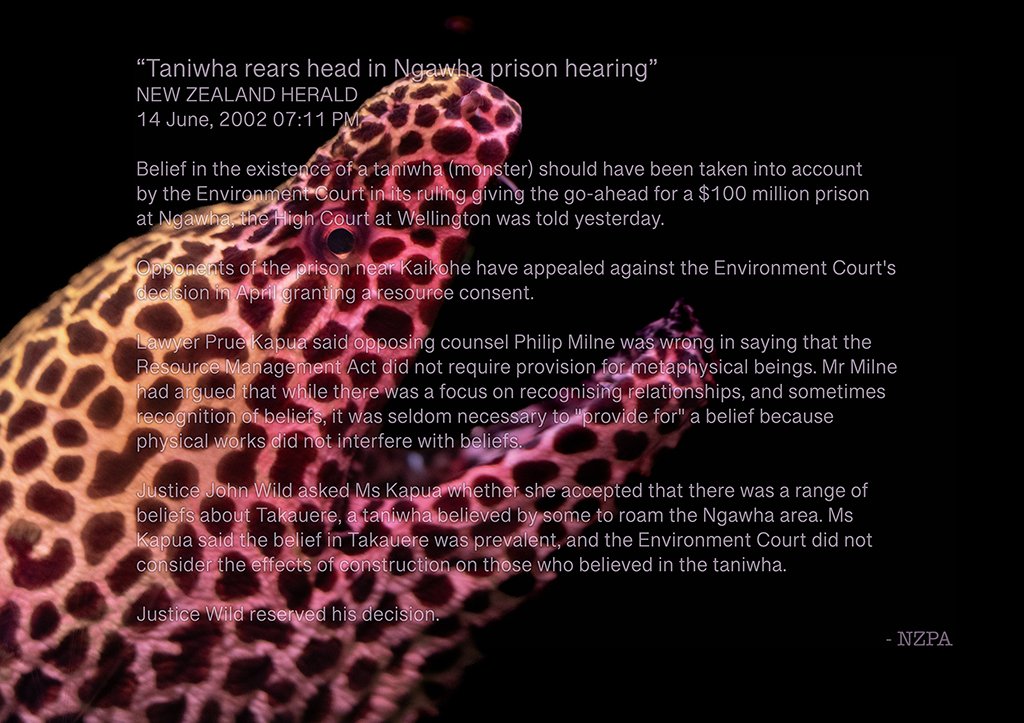

Taniwha rears head in Ngawha prison hearing

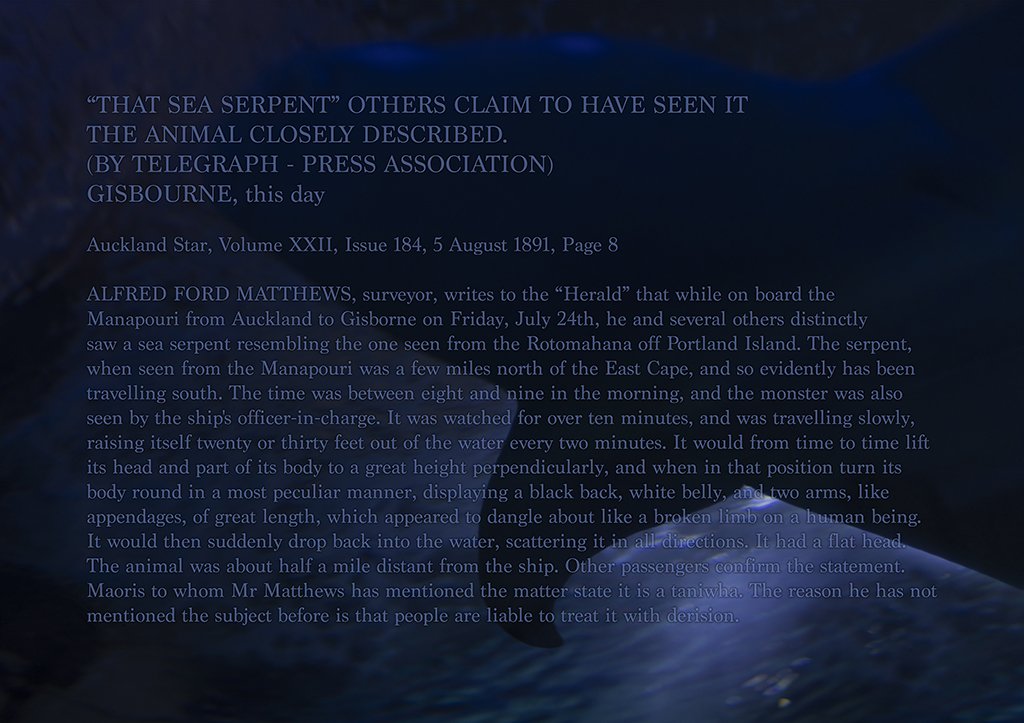

That Sea Serpent

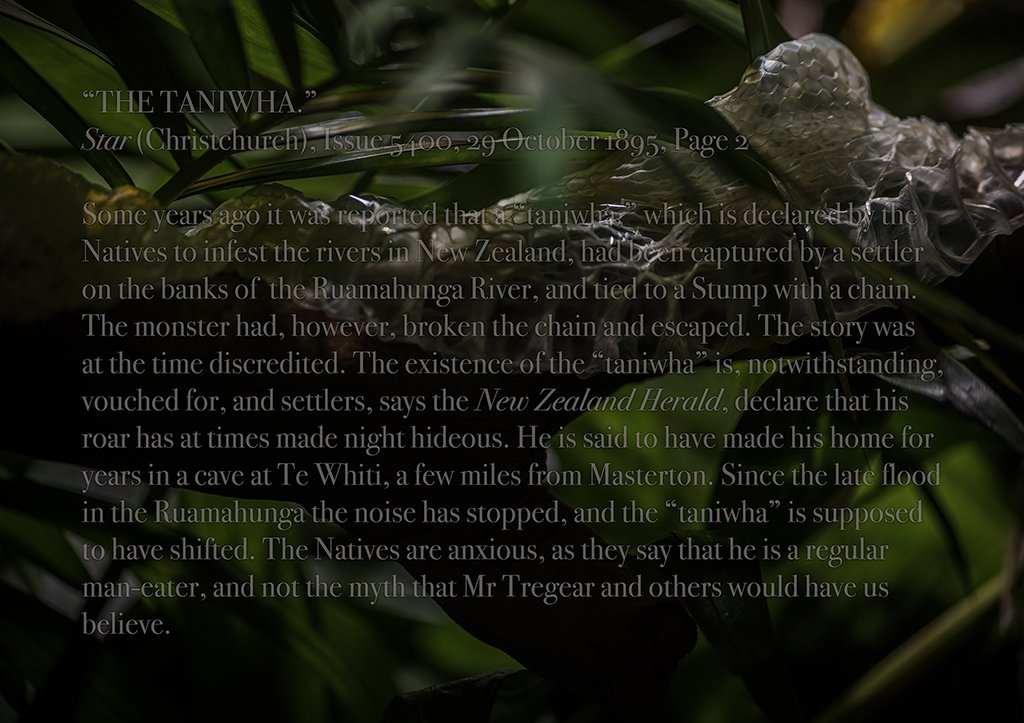

The Taniwha

The Taniwha Again

Very Like a Whale

Weird Calls to Auckland Hotline

Install image - Tarrawarra Biennial